Peyto Under Pressure

A Barometer of Climate Change

This is a science and art collaboration between the Global Water Futures artist-in-residence Gennadiy Ivanov and water expert and Global Water Futures director John Pomeroy and water expert Prof. Trevor Davies. Together, they are exploring the impacts of climate change in the circumpolar north.

Diptych, oil on canvas, 180x180cm each

Gennadiy Ivanov

Poorly Peyto

To produce this diptych, I have relied on my own field drawings and photographs, my memory, and very high-resolution stills and videos from drones operated by Global Water Futures’ scientists on that day. The meltwater was flowing in runnels and torrents across and through the ice, and parts of the glacier were dramatically colored, especially by the red of algae and the black of cryoconite (accumulations of ash and soot from wildfires, fungi, bacteria, as well as algae). At places at the margins of the Glacier, but especially below its receding snout, were deposits of yellow-tinged glacial silt. The whole scene taken together, including the bare moraines and sediment beyond the snout, summoned - in my mind - a sense of destruction.

In this diptych, the red hues signal scars which, I imagine, represent the bleeding and screaming of this ancient, moving, and ever-changing entity. Despite the vivid coloration, it represents a step closer to final death, decay, and darkness. I visualize the yellow tinges as the transformation of progressively deeper, bleeding scars to the pervasive dirty yellows which will be the remaining ice-free depositional landscape and which, for a short-time, will be desert-like in its absence of vegetation. Although Peyto must be doomed, a fate perhaps camouflaged by this transient brightness, in my future work I want to increasingly incorporate representations of potential solutions and coping strategies. In this way I want my paintings to stretch beyond the realms of awareness and engagement, and provide glimmers of hope and brightness that we have the imagination and determination to avoid the very worst consequences of climate change.

Gennadiy Ivanov

Glacier Decline

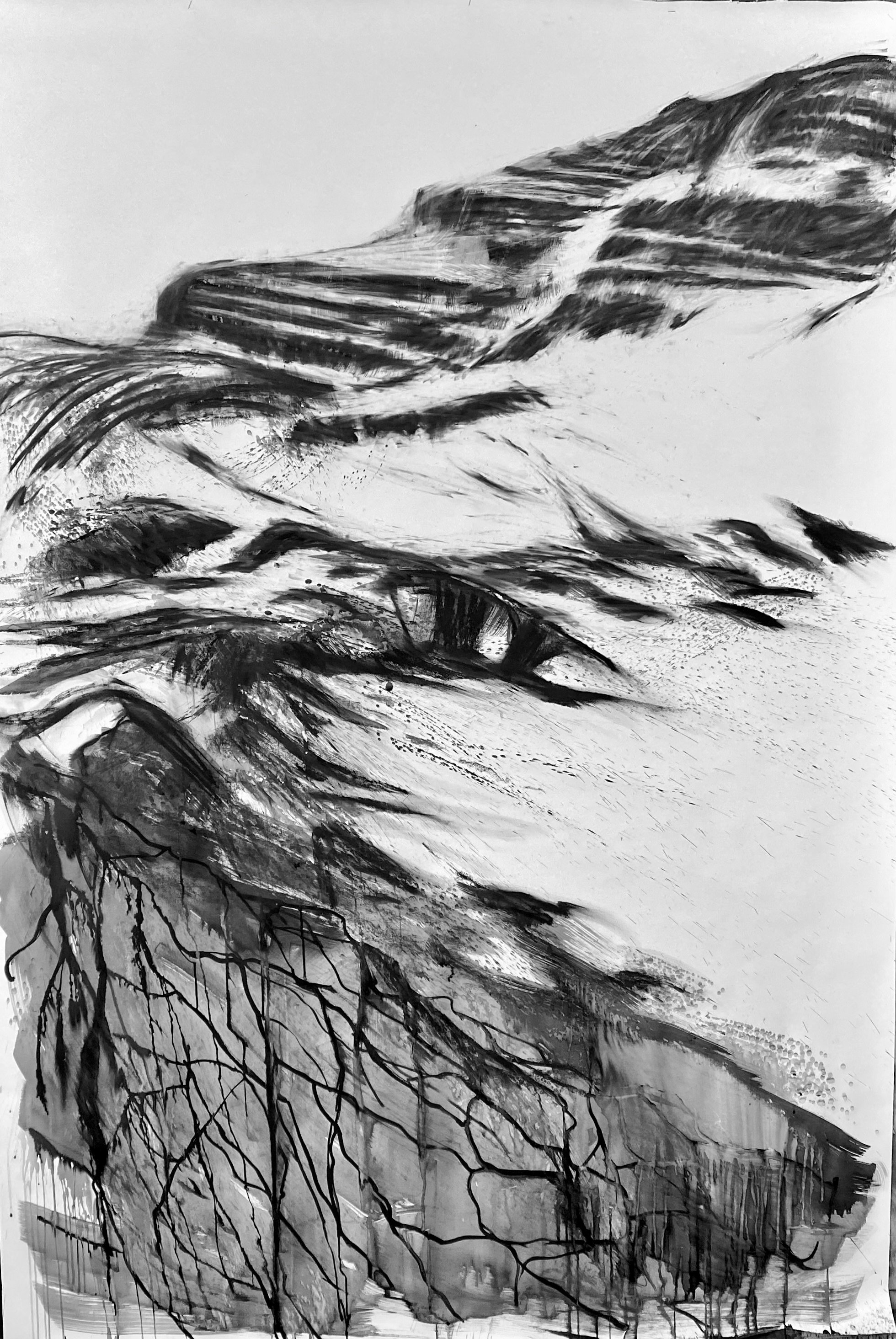

Charcoal and ink on paper, 170x100cm each

Perhaps ironically, my other paintings in the Virtual Water Gallery are amongst the most brightly-coloured I have produced in the Transitions project. One of the reasons is because on the occasion of my summer visit, in August, it was a brilliantly-clear blue sky day. My other visit was in the preceding April, on a cloudy cold grey day. The glacier was still mostly hidden beneath snow-cover. It was a miserable day; better fitting the emotions which I now feel about this departing feature of the dramatic mountain landscape. I have transposed my darker emotions into these drawings.

In the distance on the first drawing, the glacier is covered by snow. In the foreground are strange deposits of black cryoconite. The cryoconite accumulates on the ice surface and, each year, is washed off by the copious summer meltwater to form mini-mountain ranges, a metre or so high, beyond the glacier snout. Cryoconite comprises s of ash and soot from wildfires, bacteria, fungi and algae. It has become more abundant in recent years. It darkens s the glacier’s surface, reducing its reflectivity, and exacerbating melt.

The second drawing, fore-fronting the now-exposed strata which were once the side of the glacier valley are deposits of glacial silt which have accumulated below the glacier snout. I have shown how these silt deposits crack in summer heat. John Pomeroy comments “I like this drawing because it gives the illusion of the glacier transforming into a river delta – it speaks to glacial hydrology and the loss of these glaciers and their replacement by terrestrial hydrological systems. And that sediment and cracking can also be dangerous – look at India recently”.

Oil on canvas, 100x80cm

Gennadiy Ivanov

The Requiem for the Peyto

I enjoy surreal painting. It helps me express my emotions; something which is important to me. I know that scientists also have emotional responses to what they are seeing and studying. But, in their public statements, they are careful to express themselves in objective terms, based on the rational methods and reporting of science. Because I am an artist, I am allowed to portray myself in a way which expresses some of my feelings.

Here I am below the current snout of the Peyto Glacier, amidst the new and barren landscape revealed by the glacier’s rapid retreat. Modelling by the scientists shows that the glacier could have almost completely vanished by the end of the Century. Although barren, the newly-emerged post-glacial depositional landscape does show tiny specks of green – the first plants are already moving in. They are shown in my glass. Also in my glass is the beige-yellow glacial silt of the depositional landscape, and cryoconite. Cryoconite, the scientists explained to me, is a cocktail of materials which accumulates each year on the glacier’s surface. It consists of ash and soot from vegetation fires, algae, bacteria, viruses, and seeds. It has been growing in abundance over the years, accelerating the glacier’s decline, and is washed-off by the annual melt-water to form dark deposits below the snout. It aids the growth of seedlings and moss. It is an important part of the greening process, driven by the quickly-warming climate. At what point in the future will the blue-white icescape behind me be transformed to green?

I also recorded the sound of the glacier. The ice-driven katabatic wind; the wind-driven snow particles in late winter; the torrents of meltwater in summer; the splitting and crashing of the collapsing glacier. The record-player is my surreal expression of this. It is also a way, for me, to emphasise the importance of the painstaking recording of scientific data on Peyto the glacier. Observations first started more than 120 years ago, making it the longest-studied glacier in North America, and are continuing with the sophisticated instrumental network of Global Water Futures. In another 120 years there will only be the record left.

Pastel on paper, 45x65cm

Gennadiy Ivanov

Former Peyto Glacier

Here I attempt to capture the criss-cross patterns of crevasses and melt channels on the glacier; to give a sense of the collapse of the ice mass. So much of the foreground detail in this painting was hidden on my first visit to Peyton in April 2019. We walked over this landscape, but it was mainly snowcovered and frozen. In August the deposits of glacial silt and black cryoconite accumulations - surrounded by, and saturated with, water – are next-to-impossible to walkover. They give way and suck you down up to your knees; they want to drag you down. Although, again, a colorful painting, when I look at my own painting as a spectator the bare moraines and sediments left by the retreating ice giveve me a sense of destruction, darkness and decay borne in rapid deglaciation initiated by human-caused climate change. It is a disturbing task to task to try to represent the sense of decay during an azure day which produced vivid contrasts and colorations.

Oil on canvas, 150x100cm

Gennadiy Ivanov

Code Red for Peyto Glacier

As UN Secretary General António Guterres said in a recent report summarizing the science of climate change, it "is a code red for humanity". Climate scientists have said a catastrophe can be avoided if the world acts fast, and they predict that deep cuts in emissions of greenhouse gases can limit rising temperatures. However, the modest reductions in emissions promised at the COP26 Climate Summit in Glasgow were inadequate to limit climate change sufficiently to permit the survival of mountain glaciers like Peyto Glacier.

This painting shows a conceptual, blood red, lava-like flow replacing the glacier and its meltwater and the rapid, catastrophic melt of the remaining ice. Such rapid melt occurred in the record hot summer of 2021 when Peyto Glacier retreated 200m, roughly ten times its recent rate. The valley is flooded, as were many mountain rivers draining glaciers in Western Canada during the 2021 heatwave.

I have painted my reaction to this article. It is an expressionistic painting, a quick and painful reaction. So, where are we going? What is next?

“It is quite powerful and reflects the despair and horror of extreme climate change impacts on mountain cryosphere. It does portray rapid and wholesale melt very well. The ashen sky is excellent. The lava river is metaphoric and can also be interpreted as the activation of the hydrogeochemistry of the streamflow from the glacier as ice permits greater contact of water with rock, sediments and ancient deposits under the formerly glaciated headwater.” - Professor John Pomeroy

Oil on canvas, 116x81cm

Gennadiy Ivanov

Code Red for Peyto Glacier

This painting is inspired by photos I received from my GWF collaborators of the Peyto Glacier.

“You are seeing the wreckage of Peyto Glacier with its ruins floating in Lake Munro at its toe. Look how much has retreated since you last painted it. Look how dark and sooty it is after the forest fires and algae have covered it and the warmest July ever recorded melted it. Look at the gushing meltwater flowing from it, despite the day being a relatively cool and cloudy one. This is stunning physical documentation of what deglaciation looks like. There is very little ice beneath us!“ - Professor John Pomeroy

See the photo that inspired this piece under ‘The Science’ tab.

In recent decades global warming - attributable overwhelmingly to human activity - and the related changes in regional climates are having pronounced and growing impacts on many landscapes and natural systems. The cryosphere is experiencing pronounced changes. There are significant regional variations. Parts of north-west Canada are experiencing warming rates which are amongst the greatest on the planet.

The Peyto Glacier is an important focus for Global Water Futures. It is one of the valley glaciers fed by the Wapta Icefield located on the Continental Divide. It is, therefore, responding to climate signals both from the Pacific margins and the interior of the Continent. It is also the longest-studied glacier in North America, the first photographic observations being taken at the end of the 19th Century. It is a scientific benchmark study location. A detailed mass balance study was initiated in 1966. The observation program continues today with a range of sophisticated monitoring devices.

Photo credits: Phillip Harder, Centre for Hydrology, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

The glacier has lost an estimated 70% of its volume since the beginning of the 20th Century, with the most pronounced melting occurring over the last two decades. The glacier is likely to exist only in remnant form by the end of this Century, a projection based on the sort of detailed study which is described in the abstract which follows (authored by Caroline Aubry-Wake & John Pomeroy):

“Glacierized mountain areas are witnessing strong changes in their streamflow generation processes, influencing their capacity to provide crucial water resources to downstream environments. Shifting precipitation patterns, a warming climate, changing snow dynamics and retreating glaciers are occurring simultaneously, driven by complex physical feedbacks. To predict and diagnose future hydrological behaviour in these glacierized catchments, a semi-distributed, physically based hydrological model including both on and off-glacier process representation was applied used to Peyto basin, a 21 km2 glacierized alpine catchment in the Canadian Rockies. The model was forced with bias-corrected outputs from a dynamically downscaled, 4-km resolution Weather and Research Forecasting (WRF) simulation, for the 2000-2015 and 2085-2100 period. The future WRF runs had boundary conditions perturbed using RCP8.5 late century climate. The simulations show by the end-of-century, the catchment shifts from a glacial to a naval regime. The increase in precipitation nearly compensates for the decreased ice melt associated with glacier retreat, with a decrease in annual streamflow of only 7%. Peak flow shifts from July to June, and August streamflow is reduced by 68%. Changes in blowing snow transport and sublimation, avalanching, evaporation and subsurface water storage also contribute to the strong hydrological shift in the Peyto catchment. A sensitivity analysis to uncertainty in forcing meteorology reveals that streamflow volume is more sensitive to variations in precipitation whereas streamflow timing and variability are more sensitive to variations in temperature. The combination of the temperature and precipitation variations caused substantial changes both in the future snowpack and in the streamflow pattern. By including high-resolution atmospheric modelling and unprecedented both on and off-glacier process-representation in a physically based hydrological model, the results provide a particularly comprehensive evaluation of the hydrological changes occurring in high-mountain environments in response to climate change.”

Gennadiy Ivanov and Profs. John Pomeroy and Trevor Davies at St Elias Icefield, Yukon, Canada.

Gennadiy Ivanov is the artist-in-residence with the Global Water Futures program. As part of his residency, Gennadiy has been collaborating with Profs. John Pomeroy and Trevor Davies, looking at the impacts of climate change in the circumpolar north as part of the “Transitions” project.

Gennadiy’s climate-art journey started in the UK, where he was confronted with the ongoing challenge of coastal erosion. This led him to contact Prof. Trevor Davies. Prof. Trevor Davies recalls: “I was struck by Gennadiy’s paintings of the Norfolk coastline and felt that his style and imagination could work very well within a wider collaboration with scientists. If this was to be a genuine fusion of art and science, I felt we needed to understand each other's methods and techniques, and the processes which go into producing outcomes; and we needed to travel together along the route to the final representation on paper or canvas. I thought it would be beneficial for Gennadiy if he could experience and portray landscapes that were less gentle than those of Norfolk. Canada is experiencing an increasing frequency of extreme events, directly related to pronounced climate change; unprecedented floods, droughts, vegetation fires, permafrost melting, snow- and ice-cover reductions, and so on. These dramatic changes are having significant impacts on big-city infrastructure, Indigenous Peoples, agriculture.”

Gennadiy Ivanov drawing on Peyto with Profs. John Pomeroy and Trevor Davies.

“What has happened since I contacted Prof. Davies has astounded me. I have unbounded admiration for the dedication and sheer hard work of the scientists. I feel privileged to have been able to witness their important research involving sophisticated instrumentation in remote and difficult terrain in Canada. I hope my work does justice to the scientists, and adequately captures some of the challenge that is climate change.” - Gennadiy Ivanov

This collaboration soon reached an international scope, when Gennadiy Ivanov and Prof. Trevor Davies reached out to Prof. John Pomeroy:

“I was pleased to be able to invite Gennadiy to Canada to witness first-hand some of our work and some of the pronounced impacts of climate change. We have worked hard on inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in the planning of our activities, and so I was keen that Gennadiy joined our routine checking of observation stations, and saw some examples of the impacts of climate change where Indigenous Peoples are being most affected. As scientists, we were impressed with how quickly and effectively Gennadiy captured his first impressions of what he was seeing, sometimes under trying conditions. It was important that - as he produced his later and final paintings - we could come to a joint understanding of what was being portrayed. We saw this as an iterative process - a genuine working-together - and I think it has been successful.”- John Pomeroy

Once the project became embedded in the Global Water Futures programme, the team has striven to make the project as deeply interdisciplinary as possible. Artist Gennadiy Ivanov has learned something of the science behind climate change, and has joined scientists on routine research visits and measurement campaigns in Canada. He takes photographs and produces small pastel paintings in the field, often in discussion with the scientists as they go about their work. This two-way interaction is, perhaps, most rewarding when Gennadiy produces his studio paintings – based on his recollections, photographs, and field paintings. Sometimes, there are several iterations as to the best combinations of representation and interpretation to hit the two buttons: of artistic impact; and scientific coherence and message. The paintings Gennadiy produced from the first field campaign in Alberta, Yukon, and Northwest Territories in April 2019 were so well received - by the public, artists, and scientists (both within and without the Global Waters Future research programme) - that, in December 2019, Global Water Futures and the University of Saskatchewan provided financial support for a two-year term as artist-in-residence.

Profs. Pomeroy and Davies at the Wolf Creek station, Yukon, Canada.

Gennadiy Ivanov

Breakfast with scientists

Oil on canvas, 150x120cm

For artist Gennadiy Ivanov, a vital part of the “Transitions” climate-art project is the discussion with the scientists:

“This conceptualization of a breakfast conversation with Prof. John Pomeroy (left) and Prof. Trevor Davies (right) occurred the morning after our exhausting day on the Peyto Glacier in August 2019. One of the most fascinating outcomes of conversations with scientists has been my growing realization of how interconnected the world is and how something that is very small can affect the whole planet." - Gennadiy Ivanov

“I always develop strong emotional attachments to my paintings. The paintings I have produced as Global Water Futures’ artist-in-residence have invoked the strongest emotional links of any art I have ever produced. Part of that may be due to my childhood experiences in a small town near Moscow and the connections I felt to the cold snowy winters. But the main reason, I am sure, is because of my growing realization of how the world’s cold environments are being impacted by global warming - induced by human activity I have become particularly emotionally attached to the decline of the Peyto Glacier in Alberta. I will not live to see its final demise, but that event is not too far distant in the future. When scientists write they exclude emotion; their writing is rational, objective and precise. I think it is instructive to compare my artist’s language to this precise account of how scientists go about their business. Despite - or rather, because of - this, it is deeply gratifying to me that we can successfully work together on this ambitious art-science project.” - Gennadiy Ivanov

Find out more about Gennadiy Ivanov’s residency on the Global Water Futures website or on the Genadiy Ivanov’s website.

Gennadiy Ivanov is a professional artist from Norwich (Norfolk, UK) for almost 35 years now. He has a little studio-gallery in the heart of Norwich where he works and sells his artworks. He is the Global Water Future’s artist-in-residence. After attending the Norwich University of the Arts (Masters Fine Arts), Gennadiy has realized a lot of projects through which he has tried to find himself in different styles, materials and types of art: as a dancer, singer, photographer, sculpture, writer, poet and painter. You can see Gennadiy’s work with Global Water Futures on this webpage, at www.gennadiy.co.uk, on YouTube and on Facebook @Gennadiy V. Ivanov.

Professor John Pomeroy is a Distinguished Professor in the Dept. of Geography & Planning, the Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, the Director of the Global Water Futures Programme, and the Director of the University of Saskatchewan Coldwater Laboratory in Canmore (Alberta, Canada). His current research interests are on the impact of land use and climate change on cold regions hydrology and water quality, and improved prediction of climate change impacts, especially floods and droughts.

Professor Trevor Davies is Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research, Enterprise and Engagement at the University of East Anglia (UK). His research has included the deposition of atmospheric pollutants, and the links between the atmospheric transport of air pollution and meteorology and climate systems. He has planned a number of major field campaigns to examine the deposition of pollutants in, and on, snow and their incorporation into glaciers. He went on to study the significance of climate change for pollutant transport and deposition.

Contact Us!

Want to share your comments, questions or perspectives on this gallery and the themes explored? Please Contact Us!

The Virtual Water Gallery team is committed to providing a safe, respectful, harassment-free, and accessible space for all. We do not tolerate harassment of any member of society.