Summit to Sea

Head to Heart: Water as our Lifeblood

This collaborative science and art project between the Men Who Paint (Ken Van Rees, Cam Forrester, Greg Hargarten, Paul Trottier and Roger Trottier) and scientists at Global Water Futures (Colin Whitfield, Dr. Christopher Spence, Jared Wolfe, Profs. John Pomeroy and Martyn Clark) takes an encompassing approach by connecting water at the source and as it travels through the prairies and boreal forest on its way to Hudson Bay.

Ken Van Rees

Acrylic on canvas, 40x72”

Summit to Sea

The Men Who Paint have been closely connected to water as the group was formed after some discussion while floating on Emma Lake. When we started our collaborations with the scientists at the Global Water Futures, we began to reflect and realize how connected our work really has been to water whether in the mountains, prairies and boreal forest regions of Western Canada. We decided to take an encompassing approach to our project by connecting water at the source and as it travels through the prairies and boreal forest on its way to Hudson Bay. As artists, we knew that water is important to society, but after our discussions with the scientists we really began to see how critical water is to communities, industry and indigenous ways of life. Although we have seen a small snapshot of water on the landscape we paint, there are scientists who are trying to tie it altogether with computer models to look at how climate change and land use management impacts stream flows and water quality at regional scales. This painting was one way of trying to combine the connection of rivers and lakes across the mountains, prairies and boreal forest and the important concepts of water across the landscape.

Mountain Water Futures

Acrylic on canvas, 30x60”

Ken Van Rees

Hope

The Columbia Icefields are not only a major tourist attraction in the Rocky Mountains but also supply water to a number of river systems, one of which directly affects where I live in Saskatoon. Although the glaciers have been retreating there is still hope that mitigation of climate change will allow these frozen sources of water to exist in these mountain landscapes.

Ken Van Rees

Empty

Acrylic on canvas, 24x72”

In thinking about the research from the Mountain Water Futures theme and how glaciers are retreating I wanted to paint an image which represented the worst-case scenario – no more glaciers at the Columbia icefields. When we visited the Icefield Centre last fall there was a large panorama image inside that depicted all the glaciers. This is my interpretation of the icefields without glaciers and an empty parking lot representing the frightening ecological disaster of the vanished glaciers but also the social/economic impact of not having glaciers at the Columbia Icefields.

Acrylic on canvas, 36x36”

Greg Hargarten

Transfusion Donor

Fresh water is the lifeblood of everything on the planet—without it there is no life. Glaciers hold close to seventy percent of the earth’s fresh water, they are sensitive indicators of climate change and the general health of the global water supply. I wanted to paint an image that would help illustrate the contibution of glaciers to life on the planet by their delivery of fresh water in the context of water as lifeblood. I also wanted to stress the importance of the glacial health as an indicator of the earth’s health. In this painting, an abstracted aerial view, I decided to personify the glacier, giving it human features. It’s life literally melting away while it continues to support the landscape around it in a way that cannot be sustained.

Acrylic on canvas, 24x30”

Greg Hargarten

Heartland

Continuing with our theme of “Summit to Sea—Water as our Lifeblood,” I wanted to further the idea of the importance of glaciers, and how they are at the heart of our fresh water supply and very health of the earth. This abstracted aerial view shows the glacier as an actual heart pumping out the life giving water.

Acrylic on canvas, 42x60”

Paul Trottier

July Moraine

Over the years I have back packed through out Banff, Yoho and Jasper. It is always amazing during these hikes when I come across a glacier fed lake or stream. The colour of the lakes in particular seems to catch my attention. This colour is due to the presence of rock flour creating a wonderful blue/green appearance. During a family vacation to the mountains, we had the opportunity to visit Moraine Lake. Visiting the very populated site I noted that most people looked at the lake briefly and then carried on. My family spent three hours watching the changing light across this wonderful lake spot. During this time I had the opportunity to explore with camera in hand. I felt that the log jam in the foreground would help to anchor a painting-and the large log was just very interesting. As soon as I returned home I could not wait to get started on this painting from the photo’s I took. These glacier fed lakes and rivers have always had a special meaning to me-they signal a time to rest, reflect and a time to immerse.

Acrylic on canvas, 16x20”

Roger Trottier

Athabasca Glacier

The Athabasca glacier is one of six principal toes of the Columbia Icefield in the Canadian Rockies”. The icefield is the largest icefield in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. The glacier suffered from climate changes resulting in melting that has caused the size of the glacier to decrease significantly - its size shrinking to 125 square kilometres. This has meant a decrease in the amount of water that it releases across the continent. This is cause for concern from scientists and agriculturists and interested members of the public and is reason to question the wisdom of draining the prairie wetlands through ditches and canals when there is the danger of losing this valuable source of nourishment. Fortunately, the projections of the future output of snow will continue, but recent seven metre snow deposits are frighteningly diminished considered against the previous size of the outputs feeding glacier. This painting features a view from a parking lot located across from the melt-off end of the glacier tongue, just west of the icefield highway that runs by the terminus and when compared with original views of the glacier demonstrates why there should be cause for concern. I have visited this site many times over the years and it is daunting that this magnificent feature of our ecology is failing. We can only hope that current actions to offset climate changes so that actions to preserve water retention are effective.

Acrylic on Birch Board, 60x40”

Roger Trottier

Red Deer River Watershed

This mural was designed to provide a broad overview of the Red River basin showing the extent of the rivers and waters extending from the Rockies foothills to the west border of Saskatchewan where the Red River joins the South Saskatchewan. It provides a somewhat realistic illustration of the cultural activity that takes place in this Red River Watershed, showing the eco geographic features such as rivers, lakes, farmlands, industry, urban development, transportation, wildlife and human culture. The painting serves as a useful education-study device. It was reproduced as a desk size map to accompany social studies, science and cultural studies.

Prairie Water

“The three of us had a chance to visit the St. Denis National Wildlife Area in March to observe the spring melt as water from the melting snow on the surrounding hillsides fills the potholes in this area. Our interpretation of the landscape was similar but painted in different styles. We did noticed that the potholes had very little water in them from the lack of snowfall this winter and learned that this prairie pothole region is a closed system where water does not exit into rivers and lakes but infiltrates down to the water-table making these potholes an important part of the water cycle.” - Cam Forrester, Greg Hargarten and Ken Van Rees

Cam Forrester

Melt Water

Oil on panel, 11x14”

Ken Van Rees

Spring Melt in the Prairie Potholes

Acrylic on panel, 11x14”

Greg Hargarten

Connecting the Dots

Acrylic on canvas, 16x20”

Greg Hargarten

Saskatchewan Pothole

Acrylic on canvas, 12x24”

Ken Van Rees

A Duck’s Lake

Acrylic on canvas, 24x72”

This is a painting of the sloughs just south of Duck Lake that captures the various land uses from pasture to agricultural crops and shelterbelts in a typical prairie landscape. What caught my attention was all the yellow marsh ragwort around the edge of the sloughs. In the last two years I have noticed an increase in the yellow flower Marsh Ragwort plant along the shoreline of sloughs. I had a farmer tell me that he also has noticed more marsh ragwort around sloughs than he has noticed in the past.

The painting speaks nicely to the natural variability of prairie wetland systems. The abundance of marsh ragwort of late may be attributed to a return to normal or dry years after a period of high water levels as the plant is likely re-establishing itself in previously inundated areas.

Oil on canvas, 36x60”

Cam Forrester

Vanishing wetlands

The river bisects the landscape, one side showing the natural wetlands, the other side is drained cultivated agricultural lands. In the distance, the man-made canals empty in to a reservoir that has been heavily influenced by the chemicals from the runoff. The river changes from blue to green as it intersects with the water from the reservoir, affecting those downstream.

The image is based on data and information I have received through the Global Water Futures Scientists as well as other groups concerned with the loss of our prairie wetlands. Important facts that lead my outcome were: 80–90% of Saskatchewan drainage has been done illegally. 3500 drainage projects were approved with no inclusion of wetland retention. There are 2.4 million acres of unapproved drainage in Saskatchewan. 100,000–150,000 quarter sections with unapproved drainage. 1800 miles of unapproved drainage ditches.

The painting nicely encapsulates the complex nature of the practice of wetland drainage.Each side of the painting may generate a range of different perspectives. For instance, someone who wishes to maximize waterfowl habitat may interpret the left side as an ideal landscape. Those most interested in making a living in modern agriculture may see in this same side a landscape with which nothing can be done without improvement.

Acrylic on canvas, 42x60”

Paul Trottier

Bob’s Senior Moment

About ten miles out of Saskatoon and close to Meacham, is a series of prairie drainage water bodies. Located at 52 2 ’16.89 Latitude and 105 46 ’47.53 w this water body was visited and photographed by Bob Ferguson in its frozen state in the middle of winter. Struck by the depth of colour, rhythm of light and dark and function of these wetland area’s that are fundamental to the prairie ecosystem, I decided to highlight the beauty of frozen water in the middle of winter. This is a simple prairie scene that is full of reflection and story for me. It reminds me of ice fishing, cross country skiing and snowshoeing across such area’s. The wind howls, and the snow flies, but there remains a calm and warmth being close to these area’s. These area’s are a part of my sense of place and they help me to feel rooted to this place.

Paul Trottier

Water Line

Acrylic on canvas, 24x72”

After reading Dr. Pomeroy’s presentation “Estimating the impact of Wetland Drainage on Flooding in a Canadian Prairie Watershed” I reflected on how I might approach visual representation of the Prairie watershed changes. "Water line" is my interpretation of the data presented along with my history and observations on the land specifically with water changes. This is a time line in water terms, and reflects the changes that have happened since the 1950’s to 2010 and how I think it is changing the natural environment. Viewing the painting from left to right I have tried to convey how water has changed, from standing bodies to drainage systems. I purposely used rich colours on the left of the painting to show diversity and eventually moved to drab colours on the right to represent a drying of the land and an increase in streamflow. Water has a significant effect on the balance of the ecosystem and when this balance is altered it can have long lasting negative results for that ecosystem.

Boreal Water Futures

Acrylic on canvas, 36x48”

Ken Van Rees

Dodging Storm Cells

One summer we were flying to Hickson Lake to paint for a week, and I was able to sit in the cockpit of the floatplane on the trip there. I have spent a lot of time doing soil research in the boreal forest but it always amazing to see it from a different perspective. This vantage point from the floatplane revealed the myriad of lakes and streams and how water permeates these landscapes that you don’t necessarily see from the ground. This area north of Missinipe was also burned in a forest fire in 2015 depicted by the lighter green in the painting. This painting reminds me of how interconnected weather/climate is to the functioning of the boreal through water and fire. It wasn’t until I started painting the lakes that I realized that my research sites are located in the upper left corner of this painting. Funny story – I was showing this painting at a show and some people were talking about it, so I went up to talk to them about the painting and they thought it was a golf course! Interesting how perspective can change one’s perceptions of an image.

Charcoal from burnt forest on watercolor paper, 19x27”

Ken Van Rees

Musical Remnants

The past 10 years I have been exploring and interacting with burnt forests in northern Saskatchewan. The charcoal work is made in situ at the English Fire north of Prince Albert, by collecting charcoal rubbings from the standing burnt trees. Most people avoid burnt forests because they are unwelcoming places and a reminder of death and dying but fire is an essential part of maintaining the boreal forest. It’s not until you spend time in these black and dreary places that you can appreciate the changes occurring in this ecosystem. The title for this charcoal work was a result of trees making sounds when I was taking the charcoal markings off the trees onto the paper. If you look closely, you can see some stipple marks from the ‘musical’ burnt branches which reminded me of musical notes.

Mixed media on canvas, 24x36”

Ken Van Rees

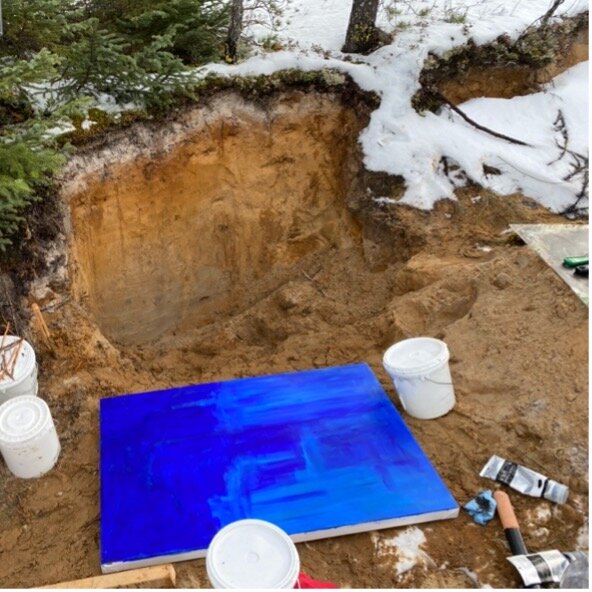

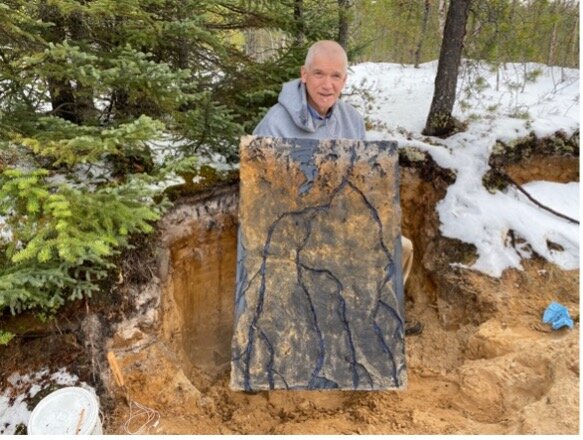

10,000 Years of Water

Water is not only important for ecosystem function and services but over time it also impacts soil development. This work is a soil imprint of an Eluviated Brunisol profile which are sandy soils commonly found with jack pine forests. Water has been percolating through this soil for 10,000 years since the icesheet retreated and created these intense colors in this profile. The top layer of the soil has turned greyish white in color due to the acid-rich water leaching elements from the soil particles in this upper A horizon. Below this bleached horizon the color has turned an intense orange-reddish color which indicates that iron in the soil has been oxidized with time. The lower horizon is a grey color and represents what the original soil looked like as it has not been influenced by the soil forming processes. Within this micro scale of the soil profile, is a network of rivers (dendritic pattern) that has been carved into the paint to reveal the blue painted ground of the canvas signifying the importance of water in ecosystems.

Mixed media on canvas, 24x30”

Ken Van Rees

Water as our Lifeblood

This is the second soil profile work that I did which is similar to the 10,000 Years of Water artwork. However, the ground painted on this canvas is orange-red to represent our blood. The network of red lines represents our veins/arteries that move blood through our bodies.

Greg Hargarten

Above Nistowiak Falls

Acrylic on canvas, 24x60”

This is painting of the area between Iskwatikan Lake and Nistowiak Lake just above the Nistowiak Falls. I’ve always wanted to visit Nistowiak Falls. They are the tallest and arguably the best known falls in Saskatchewan, but accessible only by water. We canoed from Stanley Mission on the Churchill River through Drope Lake and McMorris Bay to Jim’s camp at the base of the falls. The Churchill river is not an ordinary river but a collection of connected waterways that link the Churchill Lake, a glacial lake in northern Saskatchewan to the Hudson Bay over 1600 kilometers to the east. This area above the falls is an excellent example of the water movement in the entire northern Churchill River System. Although at times it may seem as if you are on a lake, the entire system is constantly, slowly and powerfully moving water toward Hudson Bay. It often looks peaceful and serine on the surface, but there is an under current of movement that is the life blood of the boreal world.

Acrylic on canvas, 24x24”

Greg Hargarten

Lifeblood in Reserve

I had the opportunity to paint the boreal forest north of Prince Albert in late winter/early spring. Winter brings many changes to Boreal forest areas. Much of life slows or goes into hibernation and the lakes freeze, holding their life giving water until the spring. As the warm weather arrives and the lake begins to melt, I was struck by the colour of the red-magenta ice at the shore. It seemed to be hinting at the lifeblood of water waiting to be released to breath the new life of the spring.

Acrylic on canvas, 24x30”

Paul Trottier

Black Betty Swamp

While working at the Kenderdine Campus, I had time after work each day to explore and paint the Lake land region. Over the course of several summers, I became smitten with the colours, textures and functions of bogs that dot the boreal landscape. These bogs/swamps filter the water and act as a catch basin for water collection that slowly seeps away through out the spring-fall seasons. These sites were often visited by wildlife in the later part of the day as a place to hydrate. Full of colour and reflections the swap areas became my primary focus capturing the ever changing appearance. During my last years at Emma Lake, I started to note that these specific areas were showing algae blooms early each year. On my last trip to this location I noted that in the spring the algae and the surface water plants were covering the surface-impeding the deep colours that were below and drying the swamp areas up at a quicker rate.

Acrylic on canvas, 16x20”

Roger Trottier

Culvert Rushe

The shoreline of the stream that flows into Emma Lake from north of the community of Christopher Lake (Christopher Lake is north of Prince Albert Saskatchewan). I have a particular appreciation for creek side cattails, other grasses and small shrubs that populate the shoreline, given the important purifying function provided, in particular by cattails, of removing nitrogen, phosphorous and other harmful elements that otherwise pollute natural waters.

Acrylic on canvas, 16x20”

Roger Trottier

Mayview Muskeg

This painting illustrates the water retention capacity of a muskeg like those found in the area near Emma Lake, Saskatchewan. I often see muskegs like these in my travels as I look for interesting landscape to paint and have an abiding interest in the capacity of such muskeg-like sloughs to hold waters. It is my recollections that when as a youth I worked on my grandfather’s hayfield visiting the bog areas adjacent to the creek that ran through the meadow. I remember wandering to the edges of the creek, slogging through the wet slough grasses, observing frogs and insects jumping, and colored birds fluttering through the shrubs. In my more recent hikes, I am reminded of the pleasure I experience of the wildlife and plant life I find in the wetland meadows. The setting of this painting is in the Mayview area, located just north of Shellbrook Saskatchewan.

Acrylic on canvas, 16x20”

Roger Trottier

Muskoka Marsh

This abstracted rendering of a Marsh site is suggested in this painting - a forested area where somewhat stagnant waters have collected amidst a stand of trees. A marsh is described as a wetland ecosystem where water covers the ground for long periods of time. Small shrubs often grow along the shallow edges providing a transition between water and dry land. An important function of marshes like these is the shelter and nesting sites they provide to birds, insects and small rodents. The water collection and absorption of excess nutrients that lowers oxygen levels important to wildlife is an important function of a marsh.

Acrylic on canvas, 18x22”

Roger Trottier

Marsh: Southwest Entry Gate

Highway 240 passes through the south gate of the Prince Albert National Park in northern Saskatchewan. The entry to the park crosses the Spruce river – it is thru an area of flooded meadow flats. The river passes under a bridge over the highway which gives a good view of the grass meadows that extend out from both sides of the river. The wetland and flow channel are interspersed with tongues of shoreline, floating water grasses, cattails, shrubs and trees. The meadows are quite wet, open pools of water evident throughout, providing quite adequate water reserves nourishing the foliage, and floatage. Bodies of wetland like this contribute pleasingly to the retention properties of the marsh, providing suitable feeding and nesting areas for the marine life and providing a buffer against forest fire and filtering out harmful minerals and poisons.

Mountain Water Futures

“Glacierized mountains are witnessing strong changes in their streamflow generation processes, influencing their capacity to provide runoff to support downstream water resources and ecosystems. Shifting precipitation patterns, a warming climate, changing snow dynamics and retreating glaciers are occurring simultaneously, driven by complex physical feedbacks. Simulations from coupled climate-hydrological-glacier models show that by 2100, the increase in precipitation nearly compensates the decreased ice melt associated with almost complete deglaciation, resulting in a decrease of 7% in annual streamflow. However, the timing of streamflow is drastically advanced, with peak flow shifting from July to June, and August streamflow dropping by 67%. There remains great uncertainty as to what will replace the glaciers; forests, alpine tundra; rock; ponds, lakes? The role of groundwater in sustaining mountain streamflow during droughts after deglaciation also remains highly uncertain. The simulations suggest that the much drier late summer conditions will mean that groundwater cannot compensate for the loss of glaciers and so late summer streamflows will be much lower than now.” - from Caroline Aubry-Wake and John W Pomeroy, Centre for Hydrology, University of Saskatchewan, Canmore and Saskatoon, Canada

Find out more about Mountain Water Futures.

Prairie Water

The Prairie is arguably the most intensively managed landscape in Canada. Each year millions of acres are seeded with annual crops. The climate is semi-arid to sub-humid, and weather is highly variable. Daily air temperatures range from –40°C to +40°C. The landscape is more diverse than the flat plain that is the stereotype. While there are some areas of gentle slopes, much of the region is rolling and hilly, with numerous depressions. In many of these depressions are wetlands. The Prairie Pothole Region is a portion of the Canadian Prairie with numerous wetlands that provide great value for regional water management, but can represent an opportunity cost to agricultural producers. Estimates of total wetland loss in the region range from 40-70%. Wetland loss can enhance some floods and encourage movement of nutrients and pesticides to the region’s lakes. This can increase risk of eutrophication (lake greening) and harmful algal blooms. Wetlands are focal points for groundwater recharge. It is unknown if the removal of so many wetlands reduces the sustainability of water withdrawal from underlying aquifers. The loss of wetland habitat reduces bird abundance, and biodiversity more generally, in the region. Socioeconomic incentives exist to remove some wetlands from the landscape, and decisions to remove or retain wetlands are driven by a complex suite of cultural, economic, and logistical factors.

For more information, visit the Prairie Water website.

Boreal Water Futures

In modelling the sensitivity of boreal forest river basins to drought and climate change, the withdrawal of soil water to trees through the root system and its delivery to the atmosphere and then back to the surface as rainfall is critically important. Boreal trees transpire the water they withdraw from the soil as part of photosynthesis and the transpired water vapour can then contribute to the formation of afternoon or evening convective thunderstorms. The contrast in heat between relatively cool lakes and relatively warmer forests can also contribute energy and atmospheric circulations to convective storm genesis, the rainfall from these storms can then replenish soil moisture, however lightning strikes from these storms can set forest fires. The future of a forest depends very much on whether it receives rainfall or lightning from these storms. How accurately this is described in hydrological models determines how strong the coupling between the subsurface, forests and atmospheric system is and how accurately hydrological models predict the future water supply of boreal lakes and river basins and the future evolution of the boreal landscape. These paintings beautifully capture various elements of water and energy cycling in the boreal forest, from the links between soil, roots and river to the genesis of convective storms over the patchwork of lakes and forest that characterises much of northern Canada.

Visit the Boreal Water Futures website to find out more about the science.

“Our first connection with GWF occurred March 2020 when we attended Gennadiy Ivanov’s Transition exhibition in Canmore and met a few of the water scientists at GWF. Being prairie painters, we have always loved painting in the mountains and when the opportunity happened to be a part of this pilot project we gladly said yes. We met with Dr Martyn Clark and Robert Sandford one evening last September to talk about the research results from the MWF theme and after much discussion we talked about creating a body of artwork from the ‘summit to the sea’. We then proceeded to spend a few days painting in the Canmore/Banff/Columbia icefields sites. As a scientist I have always been challenged how to present my research results to the public and this project provided an opportunity to continue my background of merging art and science.” - Ken Van Rees

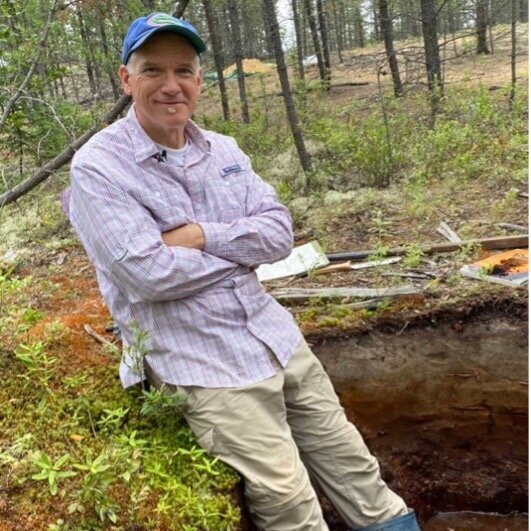

Photos of the process making the soil art, Ken Van Rees

“When we think about hydrological processes we often think about what we observe - we see glaciers crashing off a precipice, we see raging torrents of water in the mountains, we see tranquil lakes, and we experience the water on the landscape as our boots squish through sodden terrain. Our challenge in continental-domain hydrology is to rise above the landscape and consider how the juxtaposition of a myriad of processes combine in complex ways to define the terrestrial component of the global water cycle. The work of the Men Who Paint group provide us with this perspective - they vividly portray dramatic change in the landscape, and they also rise above the landscape, providing the bigger picture view of how hydrological processes are connected across the continent, and abstract interpretations how water is indeed our lifeblood. The combination of science and art in these pieces provide a beautiful illustration of both the challenges we face as scientists and the importance of our work for humanity.” - Martyn Clark

“Prairie Water is fortunate to have collaborations with the Men Who Paint group. The ‘Summit to Sea’ project that has nice synergies with the Prairie Water Project and their interests in improving resilience of communities through better understanding and communication about the importance of water resources. Online discussions among Cam, Ken and Prairie Water researchers, and attendance at regional conferences highlighted the complexity of water management in Saskatchewan, and across the Prairie. This includes key unknowns in the function of natural systems in the region, and in understanding human behaviours that can potentially alter these systems.” - Prairie Water water experts

Prairie Water also collaborated with artist Cheryl Buckmaster as part of the “Prairie Water” science and art project, showcased on the Virtual Water Gallery external projects page.

Ken Van Rees is a forest soil scientist at the University of Saskatchewan as well as a landscape painter with the plein air group the Men Who Paint. In 2004, he began a journey of using art in his soil science field courses which has led to other ecological artwork with soil pigments and charcoal from burnt forests. This GWF project has provided another avenue for him to interpret scientific results and create artworks that tell a story. You can see Van Rees’ work on the GWF webpage, at www.kenvanrees.com, on Instagram @kenvanrees or Facebook @Ken Van Rees

Greg Hargarten is a Saskatoon based painter, musician, film-maker and graphic artist. As a founding member of the “Men Who Paint” collective, he has painted across Canada and abroad. He has exhibited in over 40 solo and held in private, corporate and museum collections including The Kunstmuseum in Schwann Germany, the Parks Canada Permanent Collection, and the Mann Gallery in Prince Albert. You can see Greg’s art at www.greghargarten.com or on Instagram @greghargarten and hear his music on ricasso.ca or on YouTube

Cam Forrester retired in 2017, after 32 years in the golf and club industry. In 2005 he met a group of guys who shared the same love of outdoor landscape painting. The group, known as the “Men Who Paint”, has had the great fortune of painting in many remote areas of Canada. Cam’s paintings hang in galleries and private collections across Canada, Europe and the United States. You can connect with Cam on Facebook @Cam Forrester and on Instagram @cam.forrester. To view and/or enquire about purchasing Cam’s art: www.camforresterart.com

Paul Trottier lives and works in Saskatoon, as an artist, he has shown in numerous location across western Canada, often with the group “Men Who Paint”. A recipient of numerous accolades, Paul’s work is collected through out North America in both private and public collections. Spending his time painting across Canada, Paul is fortunate to practice his passion and experience plein air painting at its finest. Paul worked at the University of Saskatchewan for over twenty years in numerous capacities and was the past director of the internationally acclaimed Emma Lake Kenderdine Campus. Currently, Paul owns and operates Hues art supply store in Saskatoon. Professionally trained as an arts educator, Paul has also completed a Masters of Education along with numerous diploma and certificate programs. Paul loves to create, and be engaged in the pursuit of knowledge while in nature. You can connect with Paul at www.paulgtrottier.com, on Facebook @Paul Trottier or on Instagram @Paul_Trottier_

Roger Trottier is a practicing artist and arts educator. He has worked in different capacities, many related to a general interest in the arts, media production, and personal artwork as a landscape painter and illustrator. Over the years he has taught art, arts education and media studies at colleges, and universities in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Arctic Alaska. He is presently affiliated with the artist group “Men Who Paint”. Roger and the Men Who Paint have made painting excursions to National Parks and provincial parks. Roger is interested in developing visual art strategies that effectively explain scientific findings and promote good utilization practices.

Prof. John Pomeroy is Director of the Global Water Futures Programme – the largest university-led freshwater research project in the world. At the University of Saskatchewan, he is the Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, Distinguished Professor of Geography, and Director of the USask Centre for Hydrology. His primary research interests are in cold regions hydrology and water quality with an emphasis on snow redistribution and ablation processes, and the development of novel observational and modelling techniques.

Jared Wolfe is an aquatic ecologist with an interest in exploring how the interaction among science, policy, and management can establish sustainable water resources. He was the Project Manager for the Prairie Water project from 2017-2021 where he conducted research on prairie watersheds and supported the production of a virtual watershed-based modelling system for the Prairies. He also led project-wide research communication and knowledge mobilization efforts, including organizing the Annual Partners Meeting for the project. You can follow his work on Twitter @JaredWolfe76 and LinkedIn.

Colin Whitfield is an Assistant Professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability and the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan. He holds a BSc in Environmental Science (Simon Fraser University), and MSc and PhD degrees in Watershed Ecosystems (Trent University). Colin is an environmental scientist with an interest in understanding how pressures from human activities influence water resources and ecosystems, and how we can address these challenges. Colin’s research spans terrestrial to aquatic systems, including investigations of atmospheric pollution, catchment hydrochemistry, nutrient biogeochemistry, and aquatic greenhouse gas dynamics.

Dr. Christopher Spence is a research scientist for Environment and Climate Change Canada in Saskatoon. He holds adjunct professor appointments at the Universities of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. His research focuses on better understanding hydrological and hydrometeorological processes in cold regions for environmental prediction systems and policy development. His field studies are in complex landscapes such as the Canadian Shield and Prairie, as well as the Laurentian Great Lakes. Away from work, he enjoys mountain biking, backpacking, and drumming with the North Saskatchewan Regiment Pipes and Drums.

Martyn Clark is a Professor of Hydrology at the University of Saskatchewan, Associate Director of the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for Hydrology and the Canmore Coldwater Laboratory, and Fellow of the American Geophysical Union. Martyn’s research focuses in three main areas: (i) developing and evaluating process-based hydrologic models; (ii) understanding the sensitivity of water resources to climate variability and change; and (iii) developing the next generation streamflow forecasting systems. Martyn has authored or co-authored over 175 journal articles since receiving his PhD in 1998.

Contact Us!

Want to share your comments, questions or perspectives on this gallery and the themes explored? Please Contact Us!

The Virtual Water Gallery team is committed to providing a safe, respectful, harassment-free, and accessible space for all. We do not tolerate harassment of any member of society.